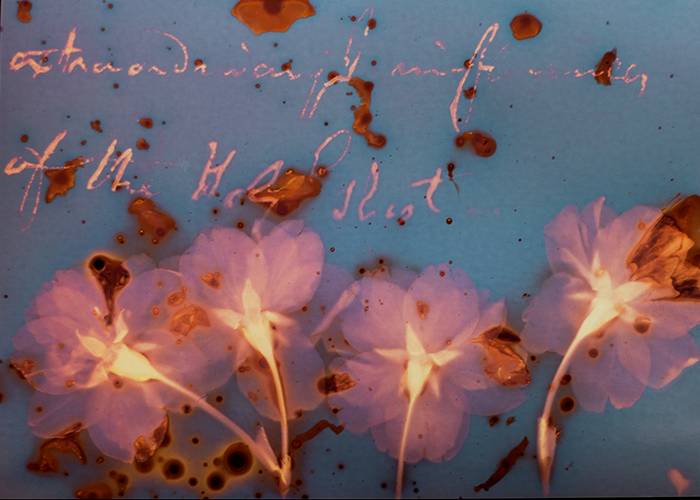

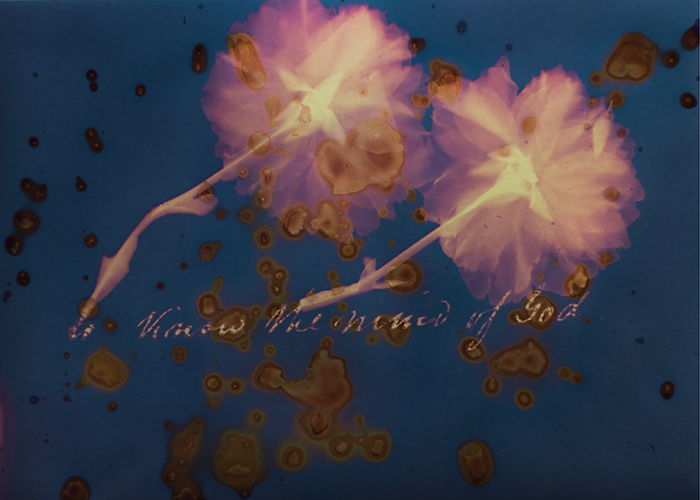

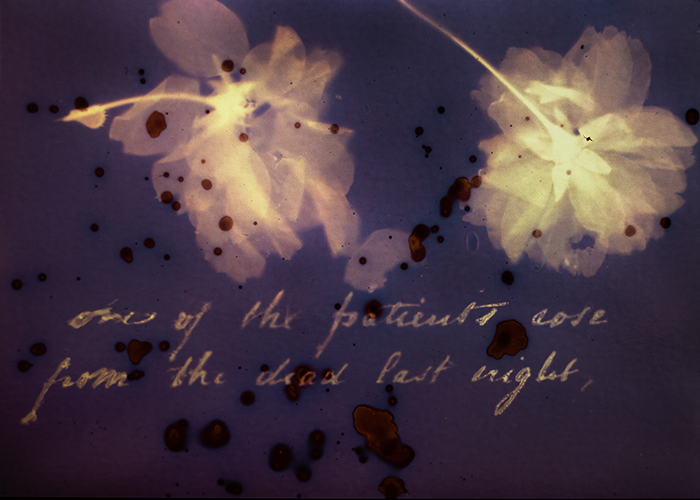

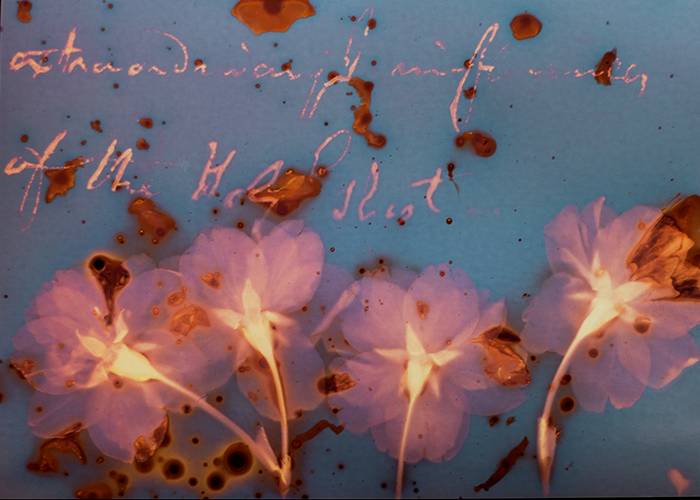

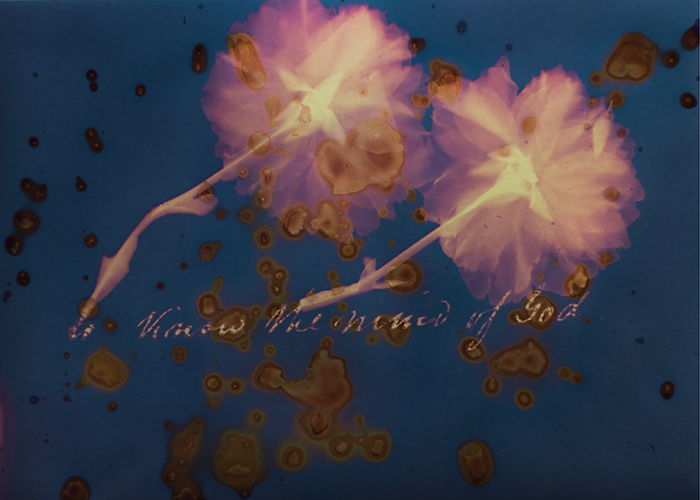

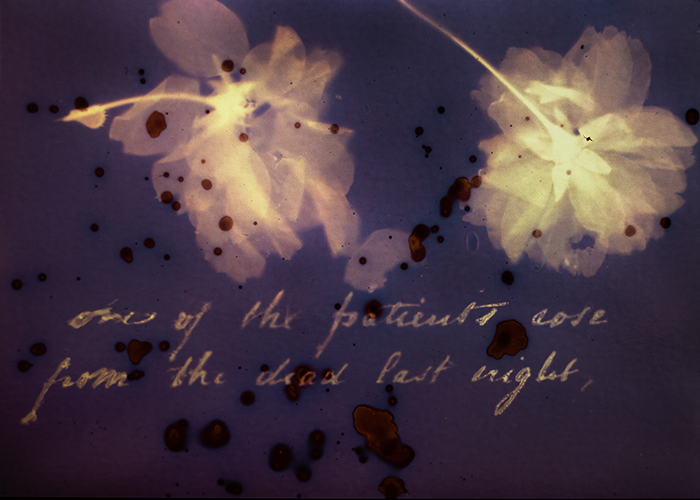

Four Lumen prints

Claire Quigley

‘extraordinary influences of the Holy Ghost’

‘to know the mind of God’

‘one of the patients rose from the dead last night’

‘tongue clean and moist’

Light-reactive photo paper, water, acetate sheets printed with extracts from a patient’s notes, and cherry blossom are pressed together under glass and exposed to sunlight. The result is a ‘lumen print’ in which only the areas hidden from the light remain bright.

The Gartnavel motto is ‘Reluceat,’ meaning ‘let there be light again’ (‘Reluceat ‘is the subjunctive form of the verb ‘reluceo,’ where the subjunctive ‘expresses an element of uncertainty, often a wish, desire, doubt or hope’).

Lumen printing is an uncertain process, with colours and images dependent on the strength of

sunlight, but it produces a picture in which darkness has been replaced by light.

Commentary

When I was sent the link to the digitized Gartnavel archive I read through some of the case studies from 1842 and was particularly struck by the one for Agnes Dow. She had been admitted several times before, most often with what was described as ‘mania,’ and had religious visions and preoccupations along with fears that people around her were trying to kill her. The entries for her admissions in previous years were fairly brief and lacking in detail although her initial admission notes, in 1829, state that she was ‘about 5 feet 1 inch high, rather stout make, round, dark countenance of rather dejected expression. Dark eyes, hair.’ They also mention that she ‘raves about religion and imagines visions of Angels and extraordinary influences of the Holy Ghost.’

In contrast the 1842 notes are very detailed and include transcripts of several things that Agnes said and of letters she wrote to clergymen that she knew through her church. From her writing it’s clear she was well educated. However, she is also trapped in a reality where patients rise from the dead, poison the food or are ‘on the lookout for corpses.’ Meanwhile, the doctors seem determined to obsessively record Agnes’s pulse, pupil-size and the state of her tongue (usually ‘clean and moist’). Obviously, these are basic physical observations, but in terms of understanding Agnes or curing her they may as well be reading signs in tealeaves or entrails.

Of course, the doctors at this point had nothing in the way of effective treatment to offer that might rescue Agnes from her situation, other than rest and time and the administration of various ‘remedies.’ With the abbreviations, Latin names and copperplate handwriting it’s hard to make out what most of them are. They include extract of gentian and bicarbonate of soda, which at least seem relatively harmless. This hadn’t been the case in previous admissions, as Agnes accuses the medics of having previously ‘muffed and jacketed’ her. It comes as no surprise that Agnes was often angry with the staff, her family, and her friends. And although a good deal of this seems entirely understandable, it was taken to be purely a symptom of her illness.

It’s difficult to find out what happened to Agnes after she left Gartnavel in September 1842, as the records are currently not indexed or transcribed. I tried to track her down using the online records at scotlandspeople.gov.uk. However the 1841 census, where she is living with her father and sister, was the only mention of her I managed to find.

Image-making Process

At the time I was reading the records I had been trying out lumen printing: an example of what’s known nowadays as an alternative process in photography. In fact lumen printing, or photogenic drawing, was the first process to produce a paper negative. The technique was created in 1834 by William Fox Talbot and involved laying objects, like flowers, leaves or lace on top of paper coated with silver nitrate and sodium chloride. The parts of the paper hidden by the object remained white, while the exposed areas darkened in sunlight.

I wanted to try and make prints from flowers or leaves combined with extracts from Agnes’s notes. I printed extracts from the notes on acetate slides and tried various methods of combining them with a variety of flowers. The results produced varied with the type of flower used, with some being too three-dimensional to flatten well and others too fragile to block enough light to produce a good image.

Adding water to the prints by wetting the paper speeded up the reaction time, creating darker areas. However it was difficult to combine water, flowers and acetates in the same layer, as the acetate was lifted off the paper by the flowers, leading to tide-marks on the image. Additionally, the ink on the acetates tended to run as they were actually designed for laser-printers not ink-jets.

In the end I flicked water over the photographic paper to create small areas of increased reactivity. The acetate with the text was then put directly onto the paper and the flowers on top of that. All the elements were then held in place under the glass in a clip-frame. To try and keep an element of similarity between the images I used cherry-blossom, which was easy to find at the time, in each one. The flowers flattened well, but the layers of petals meant that the prints retained a lot of detail and depth.

Luckily I was making the prints during a period of very sunny weather, which produced quite contrasty pictures. It became clear that, in order not to preserve the handwriting of the text and the details on the flowers, the exposure should be much shorter than the times usually recommended in books. In fact, in full sunlight at an open window the exposure was under 30 seconds.

The process itself was very compelling. It starts with trying to combine the elements to best effect in the bathroom under artificial light (the paper reacts to the ultraviolet light in sunlight). Next, taking the framed elements to an open window or outside and judging the right amount of sunlight. Then taking the frame back to the bathroom to remove everything from the frame and look at the resultant image. In many cases the image didn’t work out the way I had wanted, and I got through the best part of a pack of 100 sheets photo paper in various failed attempts.

Having photographed the prints, I then edited them in Lightroom and Photoshop. This is commonly done with lumen prints nowadays and mainly involves adjusting the ‘Curves’ settings to increase or decrease the darkness or brightness of areas of the picture.

[Patient record for Agnes Dow, HB13/5/15]

Claire Quigley lives in Glasgow where she is the STEM Coordinator for Glasgow Life. She has a PhD in computing science and has worked for Glasgow and Cambridge Universities and co-written several books on computing for publishers Dorling Kindersley. Her poems have been published in a number of magazines including Magma, Gutter and Bare Fiction.

Claire has been interested in photography since she was a child and got her first camera when she was eight years old. More recently her photos have featured on the cover of books around the world through the agency Arcangel Images. She is particularly interested in photographs that involve combining different elements, using both in-camera techniques and software.

Four Lumen prints

Claire Quigley

‘extraordinary influences of the Holy Ghost’

‘to know the mind of God’

‘one of the patients rose from the dead last night’

‘tongue clean and moist’

Light-reactive photo paper, water, acetate sheets printed with extracts from a patient’s notes, and cherry blossom are pressed together under glass and exposed to sunlight. The result is a ‘lumen print’ in which only the areas hidden from the light remain bright.

The Gartnavel motto is ‘Reluceat,’ meaning ‘let there be light again’ (‘Reluceat ‘is the subjunctive form of the verb ‘reluceo,’ where the subjunctive ‘expresses an element of uncertainty, often a wish, desire, doubt or hope’).

Lumen printing is an uncertain process, with colours and images dependent on the strength of

sunlight, but it produces a picture in which darkness has been replaced by light.

Commentary

When I was sent the link to the digitized Gartnavel archive I read through some of the case studies from 1842 and was particularly struck by the one for Agnes Dow. She had been admitted several times before, most often with what was described as ‘mania,’ and had religious visions and preoccupations along with fears that people around her were trying to kill her. The entries for her admissions in previous years were fairly brief and lacking in detail although her initial admission notes, in 1829, state that she was ‘about 5 feet 1 inch high, rather stout make, round, dark countenance of rather dejected expression. Dark eyes, hair.’ They also mention that she ‘raves about religion and imagines visions of Angels and extraordinary influences of the Holy Ghost.’

In contrast the 1842 notes are very detailed and include transcripts of several things that Agnes said and of letters she wrote to clergymen that she knew through her church. From her writing it’s clear she was well educated. However, she is also trapped in a reality where patients rise from the dead, poison the food or are ‘on the lookout for corpses.’ Meanwhile, the doctors seem determined to obsessively record Agnes’s pulse, pupil-size and the state of her tongue (usually ‘clean and moist’). Obviously, these are basic physical observations, but in terms of understanding Agnes or curing her they may as well be reading signs in tealeaves or entrails.

Of course, the doctors at this point had nothing in the way of effective treatment to offer that might rescue Agnes from her situation, other than rest and time and the administration of various ‘remedies.’ With the abbreviations, Latin names and copperplate handwriting it’s hard to make out what most of them are. They include extract of gentian and bicarbonate of soda, which at least seem relatively harmless. This hadn’t been the case in previous admissions, as Agnes accuses the medics of having previously ‘muffed and jacketed’ her. It comes as no surprise that Agnes was often angry with the staff, her family, and her friends. And although a good deal of this seems entirely understandable, it was taken to be purely a symptom of her illness.

It’s difficult to find out what happened to Agnes after she left Gartnavel in September 1842, as the records are currently not indexed or transcribed. I tried to track her down using the online records at scotlandspeople.gov.uk. However the 1841 census, where she is living with her father and sister, was the only mention of her I managed to find.

Image-making Process

At the time I was reading the records I had been trying out lumen printing: an example of what’s known nowadays as an alternative process in photography. In fact lumen printing, or photogenic drawing, was the first process to produce a paper negative. The technique was created in 1834 by William Fox Talbot and involved laying objects, like flowers, leaves or lace on top of paper coated with silver nitrate and sodium chloride. The parts of the paper hidden by the object remained white, while the exposed areas darkened in sunlight.

I wanted to try and make prints from flowers or leaves combined with extracts from Agnes’s notes. I printed extracts from the notes on acetate slides and tried various methods of combining them with a variety of flowers. The results produced varied with the type of flower used, with some being too three-dimensional to flatten well and others too fragile to block enough light to produce a good image.

Adding water to the prints by wetting the paper speeded up the reaction time, creating darker areas. However it was difficult to combine water, flowers and acetates in the same layer, as the acetate was lifted off the paper by the flowers, leading to tide-marks on the image. Additionally, the ink on the acetates tended to run as they were actually designed for laser-printers not ink-jets.

In the end I flicked water over the photographic paper to create small areas of increased reactivity. The acetate with the text was then put directly onto the paper and the flowers on top of that. All the elements were then held in place under the glass in a clip-frame. To try and keep an element of similarity between the images I used cherry-blossom, which was easy to find at the time, in each one. The flowers flattened well, but the layers of petals meant that the prints retained a lot of detail and depth.

Luckily I was making the prints during a period of very sunny weather, which produced quite contrasty pictures. It became clear that, in order not to preserve the handwriting of the text and the details on the flowers, the exposure should be much shorter than the times usually recommended in books. In fact, in full sunlight at an open window the exposure was under 30 seconds.

The process itself was very compelling. It starts with trying to combine the elements to best effect in the bathroom under artificial light (the paper reacts to the ultraviolet light in sunlight). Next, taking the framed elements to an open window or outside and judging the right amount of sunlight. Then taking the frame back to the bathroom to remove everything from the frame and look at the resultant image. In many cases the image didn’t work out the way I had wanted, and I got through the best part of a pack of 100 sheets photo paper in various failed attempts.

Having photographed the prints, I then edited them in Lightroom and Photoshop. This is commonly done with lumen prints nowadays and mainly involves adjusting the ‘Curves’ settings to increase or decrease the darkness or brightness of areas of the picture.

[Patient record for Agnes Dow, HB13/5/15]

Claire Quigley lives in Glasgow where she is the STEM Coordinator for Glasgow Life. She has a PhD in computing science and has worked for Glasgow and Cambridge Universities and co-written several books on computing for publishers Dorling Kindersley. Her poems have been published in a number of magazines including Magma, Gutter and Bare Fiction.

Claire has been interested in photography since she was a child and got her first camera when she was eight years old. More recently her photos have featured on the cover of books around the world through the agency Arcangel Images. She is particularly interested in photographs that involve combining different elements, using both in-camera techniques and software.