Walking the Archive: Walk-wall-well

Dee Heddon

Re-creational Routes

A series of walking scores for interpretation, inspired by Margaret S. or G.

It’s ‘Wait’, ‘Wait’, ‘Wait’, – Till a stupid Nurse opens the door,

And then you’ve to wait again at the gate, – The system is rot to the core.

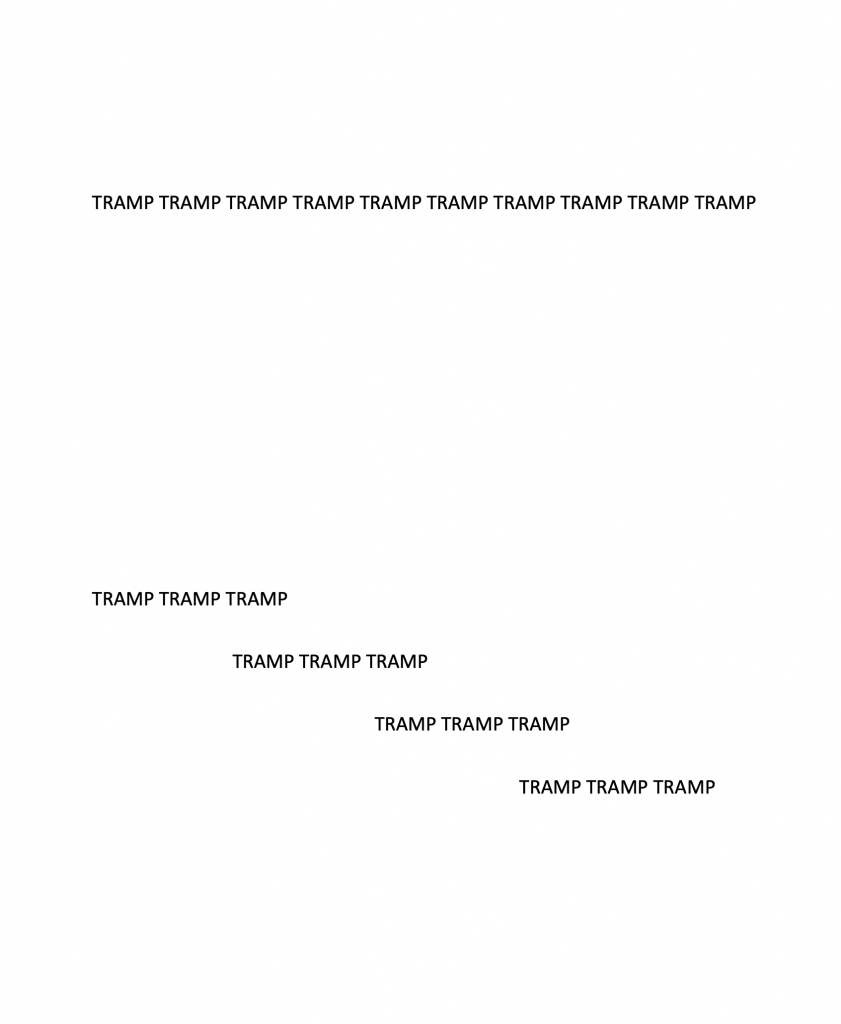

It’s tramp, tramp, tramp, – Till a silly Nurse gives you the word

To ‘turn’ or to ‘stop’ or ‘sit down’ with a plop, – The whole wretched fad is absurd.

Commentary

Finding Gartnavel

I have always been a walker. Not anything grand, like a hillwalker, or a hiker, just someone who likes and tries to walk daily, aiming for 10,000 steps. Like many, during the first COVID-19 lockdown I was increasingly bored with my routine paths, and frustrated at how busy they became. I began to seek out new (to me) places (making them busier in turn). One of my discoveries was Gartnavel, located a whole 1.3 miles north of my house. My first visit was a revelation – the extensive grounds, the grand trees, the impressive, crumbling architecture, the open views across to the Campsies, the walking paths, and the most magical Walled Garden.

I wasn’t alone in seeking respite and taking solace in Gartnavel’s landscaped grounds. A recent newsletter from NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde reported that since the lockdown in March 2020, ‘footfall to the hospital grounds increased by around 500%’. Reading the information boards scattered across its grounds on that first visit, I learnt that even in its first incarnation, Gartnavel recognised the importance of fresh air, green spaces, and exercise to wellbeing: ‘Wards were surrounded by exercise yards and flower gardens with seats and shelters.’ The information boards are not just historical though; they command me to ‘Take Time Out’ by exploring the grounds because ‘A brisk walk clears your head and keeps you fit.’ I find a painted stone near one of the paths which seems to signal to better days, hopefully those still to come.

Writing the Asylum

Coinciding with the invitation to participate in Writing the Asylum, is a research project I am leading which explores people’s experiences of walking during COVID-19, and whether they encountered creative walking activities, such as painted stone trails or chalked messages on walls and pavements (see www.walkcreate.org). Our online public survey revealed just how vital walking had been to many people, one respondent even referring to it as a lifeline. Walking offered exercise, escape, routine, space, time, distraction, focus, interest, solitude, and companionship. It was inevitable that the lens and practice through which I have engaged with Gartnavel’s archives was walking.

The two archival documents Gillean selected to share with me were Gartnavel Royal Hospital: Conservation Audit (of 1843 buildings) compiled by Simpson & Brown Architects (July 2009) and Let There Be Light Again: A History of Gartnavel Hospital From its Beginnings to the Present Day, eds., Jonathan Andrews and Iain Smith (1993). There is little detailed information about walking. I noted that:

– the laying of the foundation stone on 1 June 1842 was marked by a grand procession, complete with full military band and a regiment of artillery, leading from the City Hall in Candleriggs to Gartnavel.

– the provision of a regular water supply had been a challenge for the Asylum and in times of severe shortage, water was taken from the River Kelvin, behind the Botanic Gardens, and carted all the way up Great Western Rd by patients and staff.

– airing grounds or airing yards, outdoor spaces in which inmates could exercise, were attached to each ward. The quality of these varied according to status, with those for higher fee-paying patients ‘turfed and planted with shrubs’ and offering shaded seats, while the male paupers’ ground, by contrast, was described in 1826, as being in a ‘very miry state’, and requiring ‘extensive drainage and relaying with gravel’.

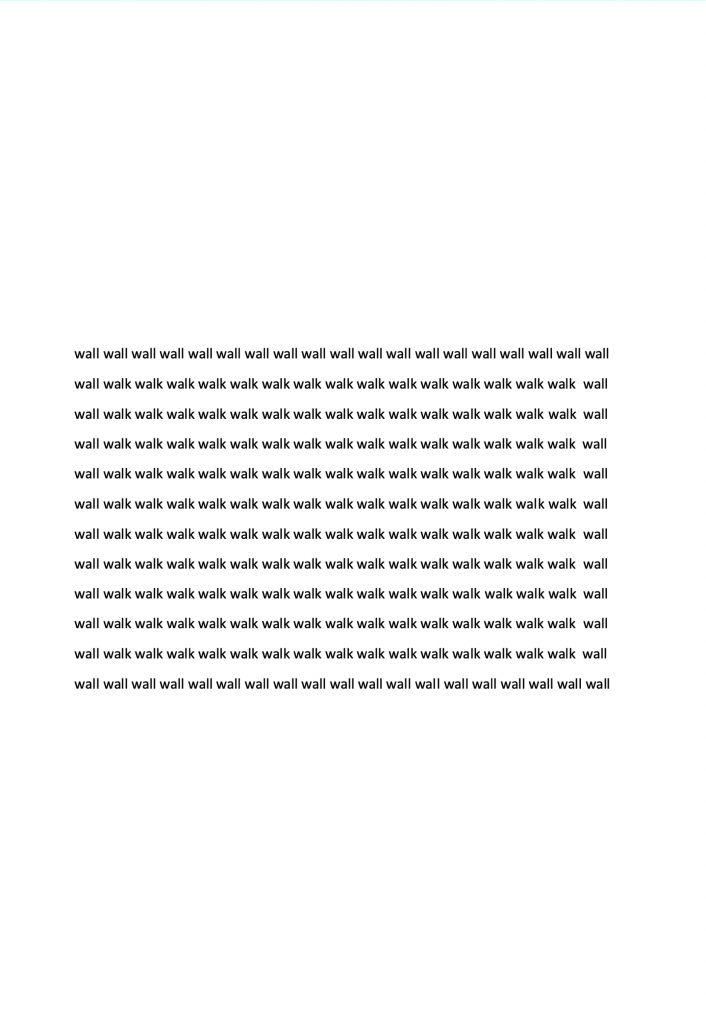

– the risk of escape offered by airing grounds was mitigated by the posting of a watchkeeper on the Asylum’s roof, later replaced by increasing the airing grounds’ walls and digging ditches at their base.

Stepping (into) the Archive

I supplement my reading by walking around Gartnavel site, stepping (into) the archive. The institutional commitment to green recovery can be felt tacitly in the architecture and landscaping, much of which endures nearly 180 years later. Gartnavel, with its still-sweeping driveways, vistas and stately-home façade, represents what geographer Chris Philo terms a ‘moral geography’.* The location itself was deemed to be therapeutic not only because of the contemplative ‘retreat’ it offered from the industrialised city, but also through the recreational and occupational activity it afforded, key amongst which was daily exercise. Inmates in asylums such as Gartnavel were expected to engage in such recreation, not just because it was felt to be good for their recovery, but also because such engagement was itself the very performance of that recovery. When one was deemed well enough, daily exercise extended beyond the walled airing grounds into the wider asylum environment.

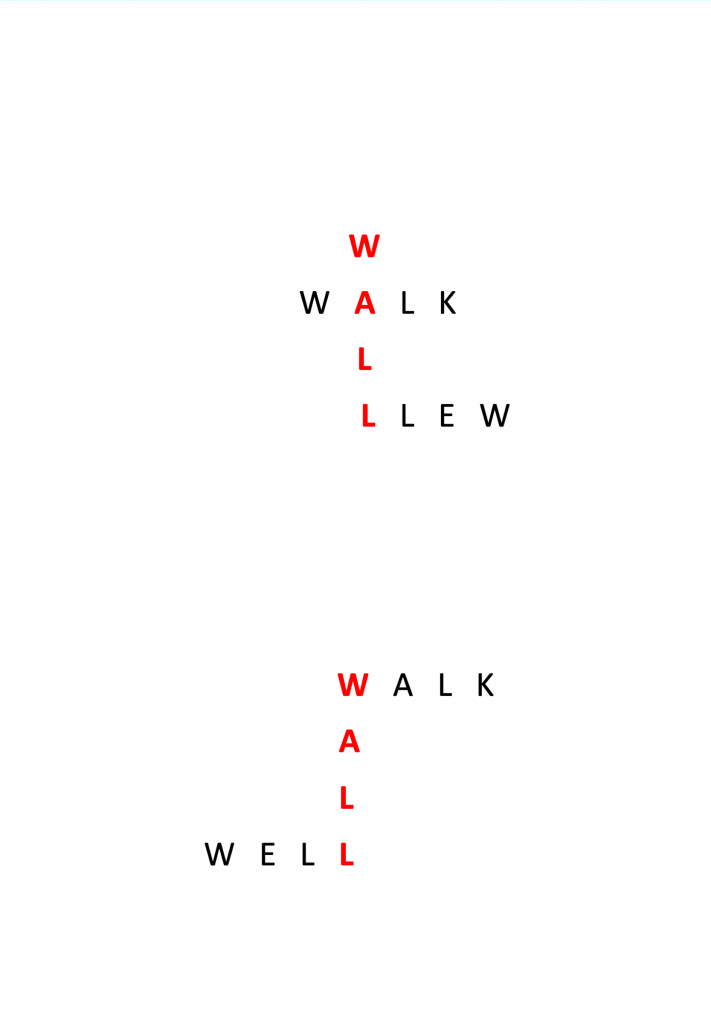

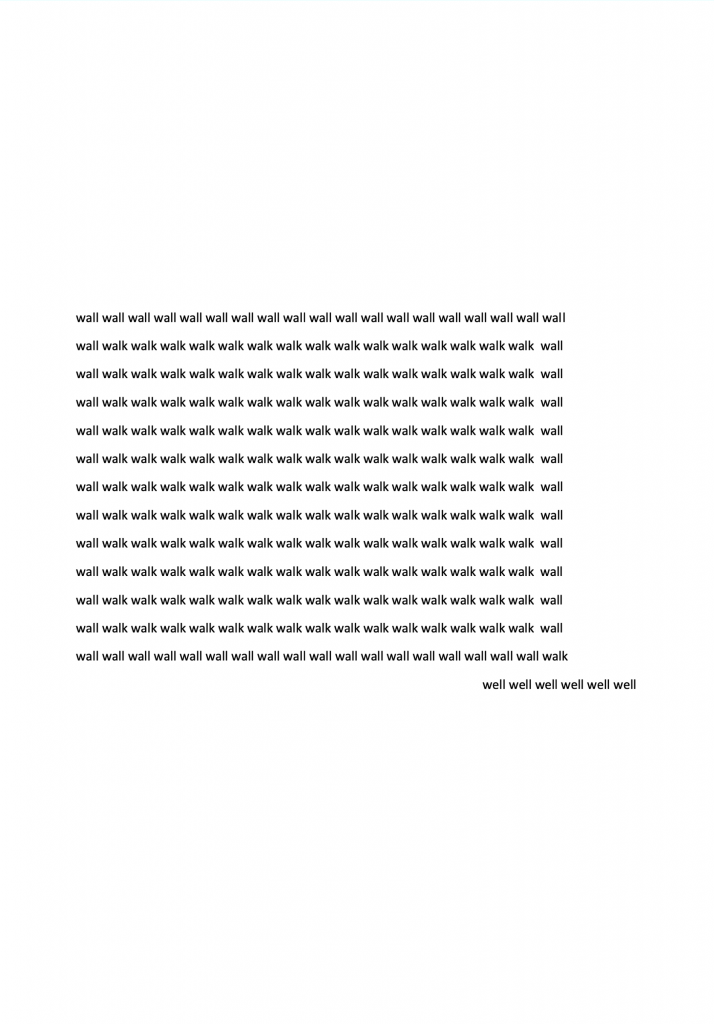

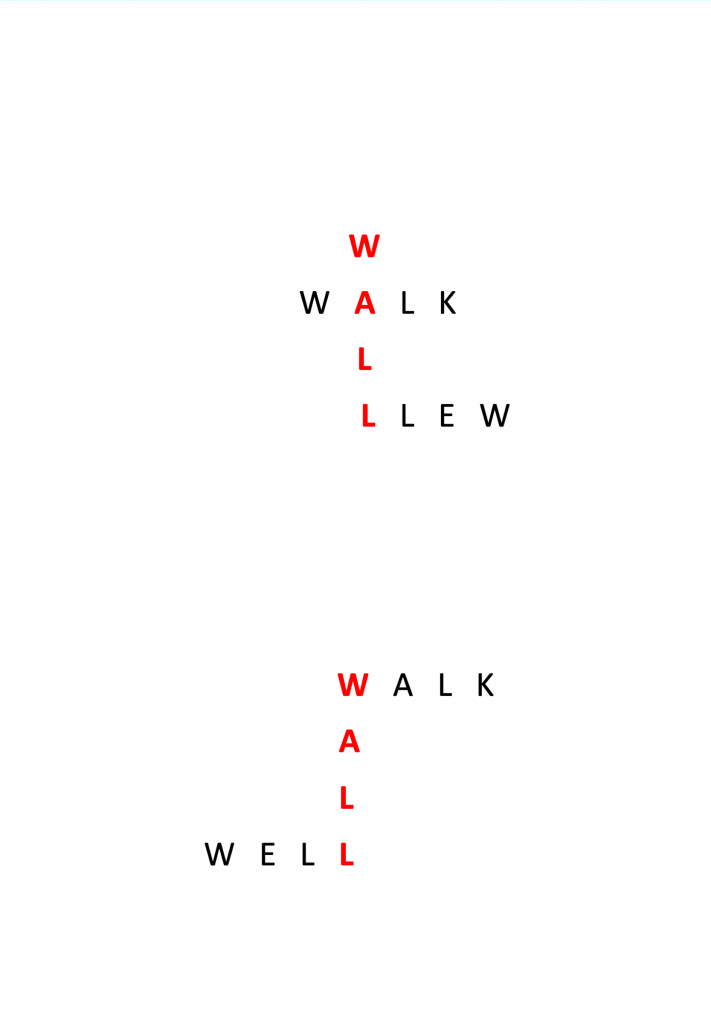

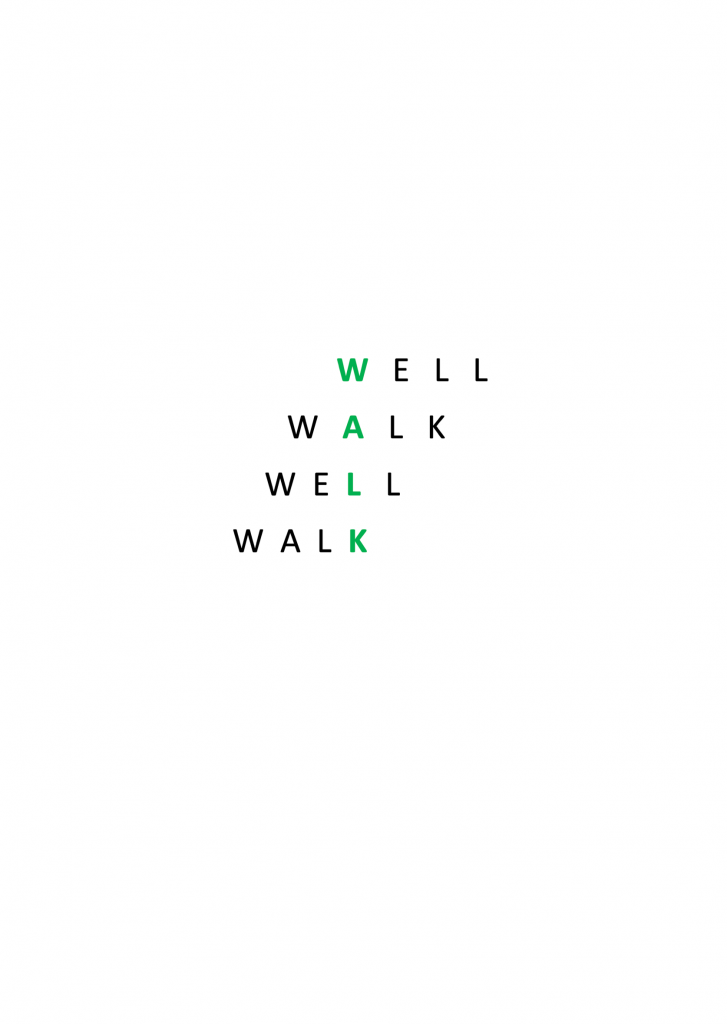

Walk-wall-well.

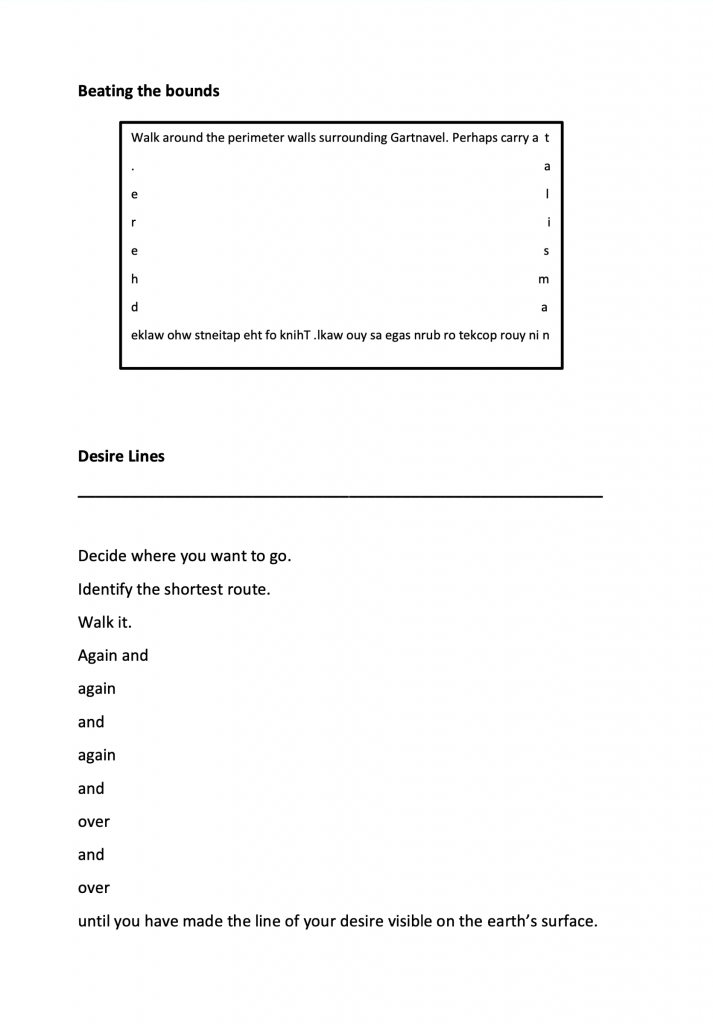

Though there are few accounts in the case notes of patients being forced to exercise, the ditty by inmate Margaret S. or G., which heads up my creative response, suggests a degree of implicit coercion. I carry an uncomfortable tension as I walk the grounds of Gartnavel, acknowledging walking’s centrality to my own and others’ mental wellbeing and its potential diminishment when cast as moral imperative. I walk thinking of walking as both a command and route to freedom.

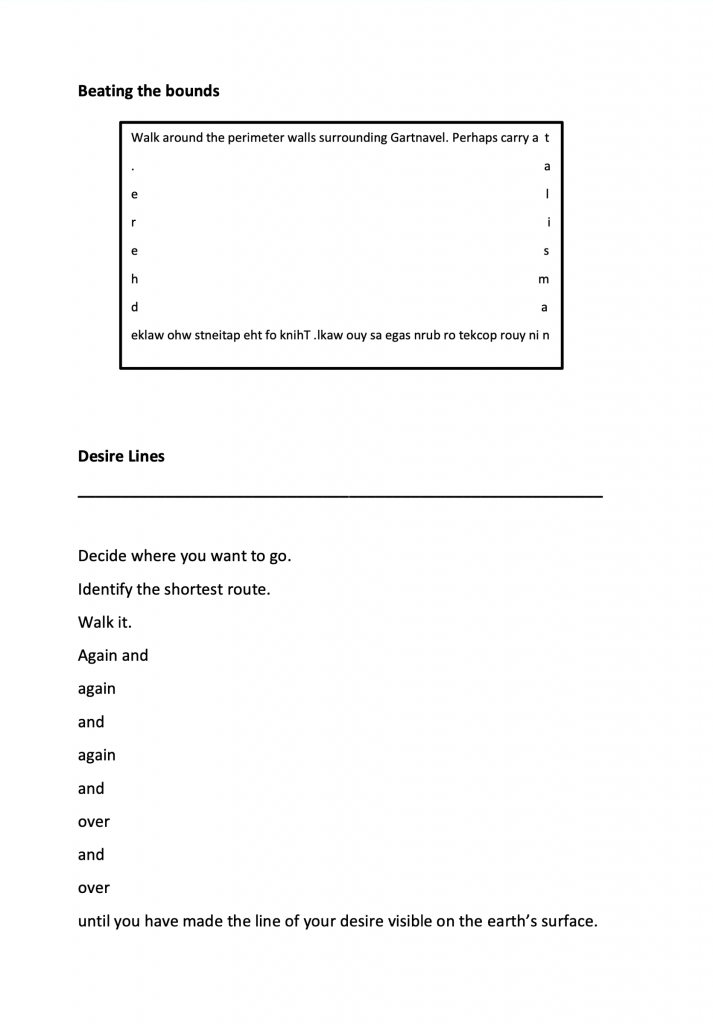

I beat the bounds of the perimeter walls, haunted by the footsteps of others, and wish them peace on their future journeys.

I look for desire lines and tramp my own down a hill that plots my way out. It takes 30,000 repeated steps – 3 days x 10,000 – to mark my intention. The repetition transforms the pleasure of walking into drudgery, but the feeling of freedom once the path is made and I follow it down and then out is tangible, legs sore but pleasure returned.

Desire paths, Gartnavel

* Chris Philo, A Geographical History of Institutional Provision for the Insane from the Medieval Times to the 1980s in England and Wales: The Space Reserved for Insanity, Edwin Mellen Press, 2004, p. 592.

[Gartnavel Royal Hospital: Conservation Audit (of 1843 buildings) compiled by Simpson & Brown Architects for commissioning clients NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde (July 2009), and patient notes for Margaret S. or G. (1900s) cited in Let There Be Light Again: A History of Gartnavel Hospital From its Beginnings to the Present Day, eds., Jonathan Andrews and Iain Smith (1993, p. 116)].

Dee Heddon holds the James Arnott Chair in Drama at the University of Glasgow. She has been exploring walking as a creative practice for more than a decade, and has published on it widely, as well as engaged in creative research through her ongoing project The Walking Library (https://walkinglibraryproject.wordpress.com) She is currently leading a research project exploring people’s experiences of walking during COVID-19, alongside artists’ use of walking as creative resource during the pandemic (www.walkcreate.org). (Author photograph by Martin Shields)

Walking the Archive: Walk-wall-well

Dee Heddon

Re-creational Routes

A series of walking scores for interpretation, inspired by Margaret S. or G.

It’s ‘Wait’, ‘Wait’, ‘Wait’, – Till a stupid Nurse opens the door,

And then you’ve to wait again at the gate, – The system is rot to the core.

It’s tramp, tramp, tramp, – Till a silly Nurse gives you the word

To ‘turn’ or to ‘stop’ or ‘sit down’ with a plop, – The whole wretched fad is absurd.

Commentary

Finding Gartnavel

I have always been a walker. Not anything grand, like a hillwalker, or a hiker, just someone who likes and tries to walk daily, aiming for 10,000 steps. Like many, during the first COVID-19 lockdown I was increasingly bored with my routine paths, and frustrated at how busy they became. I began to seek out new (to me) places (making them busier in turn). One of my discoveries was Gartnavel, located a whole 1.3 miles north of my house. My first visit was a revelation – the extensive grounds, the grand trees, the impressive, crumbling architecture, the open views across to the Campsies, the walking paths, and the most magical Walled Garden.

I wasn’t alone in seeking respite and taking solace in Gartnavel’s landscaped grounds. A recent newsletter from NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde reported that since the lockdown in March 2020, ‘footfall to the hospital grounds increased by around 500%’. Reading the information boards scattered across its grounds on that first visit, I learnt that even in its first incarnation, Gartnavel recognised the importance of fresh air, green spaces, and exercise to wellbeing: ‘Wards were surrounded by exercise yards and flower gardens with seats and shelters.’ The information boards are not just historical though; they command me to ‘Take Time Out’ by exploring the grounds because ‘A brisk walk clears your head and keeps you fit.’ I find a painted stone near one of the paths which seems to signal to better days, hopefully those still to come.

Writing the Asylum

Coinciding with the invitation to participate in Writing the Asylum, is a research project I am leading which explores people’s experiences of walking during COVID-19, and whether they encountered creative walking activities, such as painted stone trails or chalked messages on walls and pavements (see www.walkcreate.org). Our online public survey revealed just how vital walking had been to many people, one respondent even referring to it as a lifeline. Walking offered exercise, escape, routine, space, time, distraction, focus, interest, solitude, and companionship. It was inevitable that the lens and practice through which I have engaged with Gartnavel’s archives was walking.

The two archival documents Gillean selected to share with me were Gartnavel Royal Hospital: Conservation Audit (of 1843 buildings) compiled by Simpson & Brown Architects (July 2009) and Let There Be Light Again: A History of Gartnavel Hospital From its Beginnings to the Present Day, eds., Jonathan Andrews and Iain Smith (1993). There is little detailed information about walking. I noted that:

– the laying of the foundation stone on 1 June 1842 was marked by a grand procession, complete with full military band and a regiment of artillery, leading from the City Hall in Candleriggs to Gartnavel.

– the provision of a regular water supply had been a challenge for the Asylum and in times of severe shortage, water was taken from the River Kelvin, behind the Botanic Gardens, and carted all the way up Great Western Rd by patients and staff.

– airing grounds or airing yards, outdoor spaces in which inmates could exercise, were attached to each ward. The quality of these varied according to status, with those for higher fee-paying patients ‘turfed and planted with shrubs’ and offering shaded seats, while the male paupers’ ground, by contrast, was described in 1826, as being in a ‘very miry state’, and requiring ‘extensive drainage and relaying with gravel’.

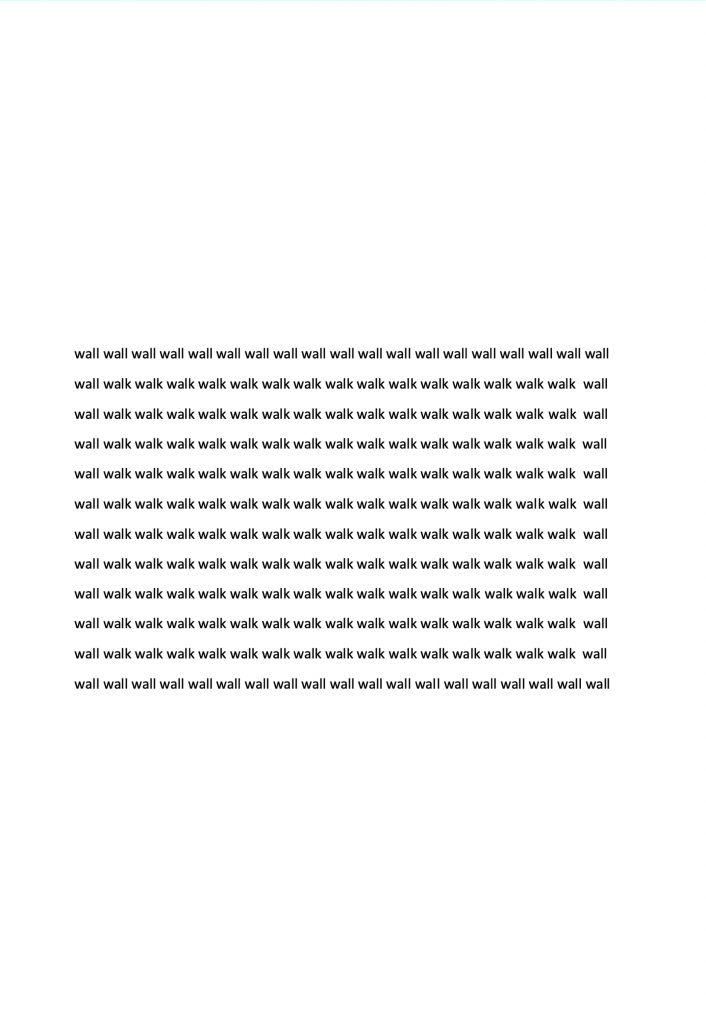

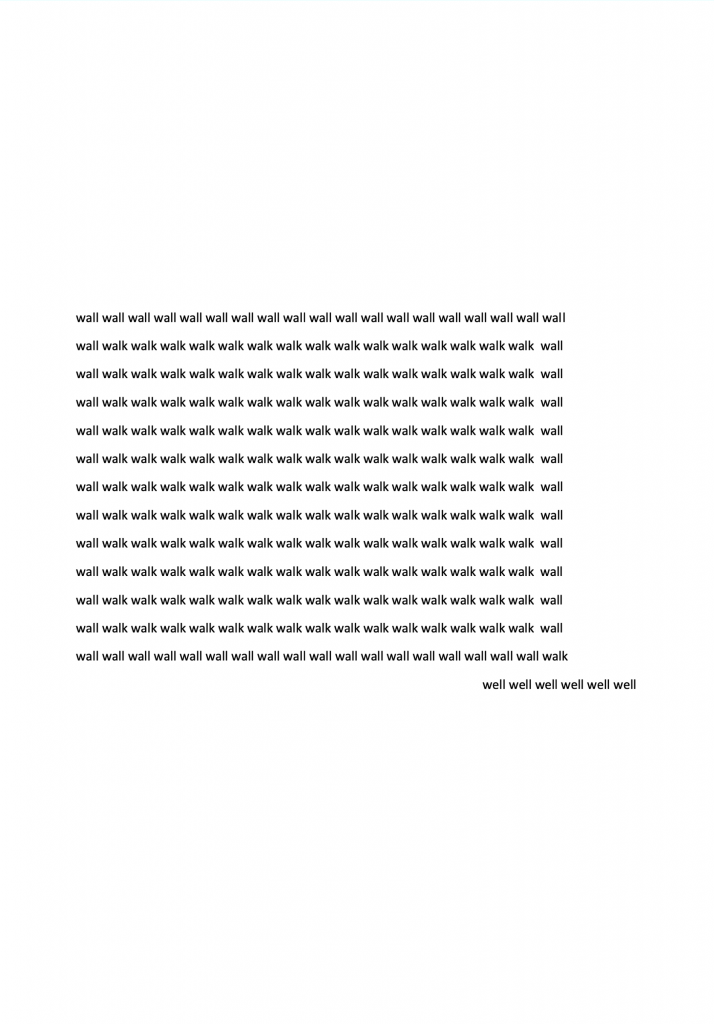

– the risk of escape offered by airing grounds was mitigated by the posting of a watchkeeper on the Asylum’s roof, later replaced by increasing the airing grounds’ walls and digging ditches at their base.

Stepping (into) the Archive

I supplement my reading by walking around Gartnavel site, stepping (into) the archive. The institutional commitment to green recovery can be felt tacitly in the architecture and landscaping, much of which endures nearly 180 years later. Gartnavel, with its still-sweeping driveways, vistas and stately-home façade, represents what geographer Chris Philo terms a ‘moral geography’.* The location itself was deemed to be therapeutic not only because of the contemplative ‘retreat’ it offered from the industrialised city, but also through the recreational and occupational activity it afforded, key amongst which was daily exercise. Inmates in asylums such as Gartnavel were expected to engage in such recreation, not just because it was felt to be good for their recovery, but also because such engagement was itself the very performance of that recovery. When one was deemed well enough, daily exercise extended beyond the walled airing grounds into the wider asylum environment.

Walk-wall-well.

Though there are few accounts in the case notes of patients being forced to exercise, the ditty by inmate Margaret S. or G., which heads up my creative response, suggests a degree of implicit coercion. I carry an uncomfortable tension as I walk the grounds of Gartnavel, acknowledging walking’s centrality to my own and others’ mental wellbeing and its potential diminishment when cast as moral imperative. I walk thinking of walking as both a command and route to freedom.

I beat the bounds of the perimeter walls, haunted by the footsteps of others, and wish them peace on their future journeys.

I look for desire lines and tramp my own down a hill that plots my way out. It takes 30,000 repeated steps – 3 days x 10,000 – to mark my intention. The repetition transforms the pleasure of walking into drudgery, but the feeling of freedom once the path is made and I follow it down and then out is tangible, legs sore but pleasure returned.

Desire paths, Gartnavel

* Chris Philo, A Geographical History of Institutional Provision for the Insane from the Medieval Times to the 1980s in England and Wales: The Space Reserved for Insanity, Edwin Mellen Press, 2004, p. 592.

[Gartnavel Royal Hospital: Conservation Audit (of 1843 buildings) compiled by Simpson & Brown Architects for commissioning clients NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde (July 2009), and patient notes for Margaret S. or G. (1900s) cited in Let There Be Light Again: A History of Gartnavel Hospital From its Beginnings to the Present Day, eds., Jonathan Andrews and Iain Smith (1993, p. 116)].

Dee Heddon holds the James Arnott Chair in Drama at the University of Glasgow. She has been exploring walking as a creative practice for more than a decade, and has published on it widely, as well as engaged in creative research through her ongoing project The Walking Library (https://walkinglibraryproject.wordpress.com) She is currently leading a research project exploring people’s experiences of walking during COVID-19, alongside artists’ use of walking as creative resource during the pandemic (www.walkcreate.org). (Author photograph by Martin Shields)