Grace Binning responds

R Fraser

Conversation with the Devil

Daily Diagnosis

Cut, Tear, Scratch

Confined

An Address from Your Queen

Thank you Letter to My Sister (For My Immediate Removal)

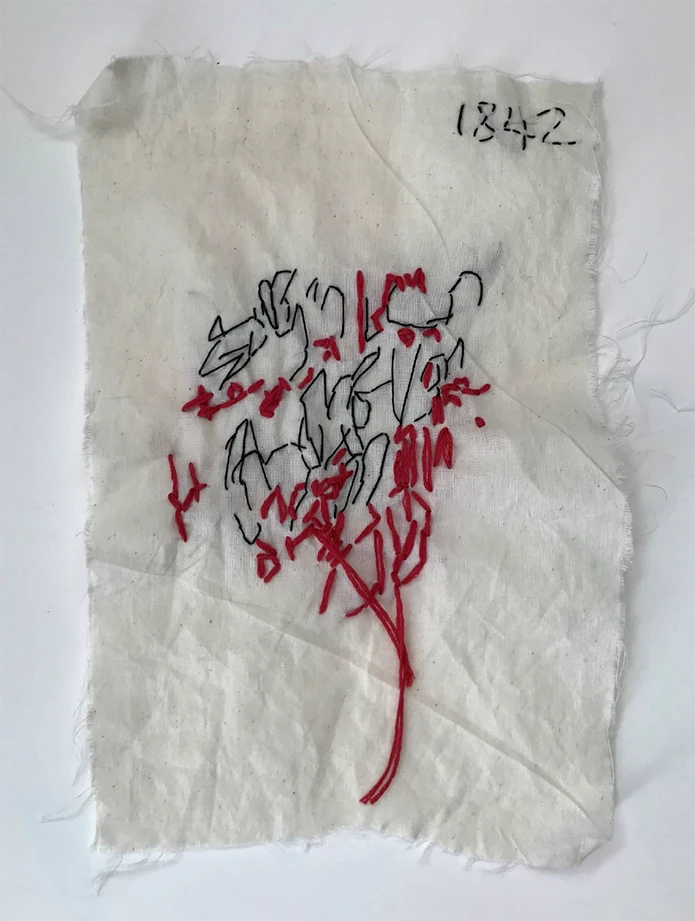

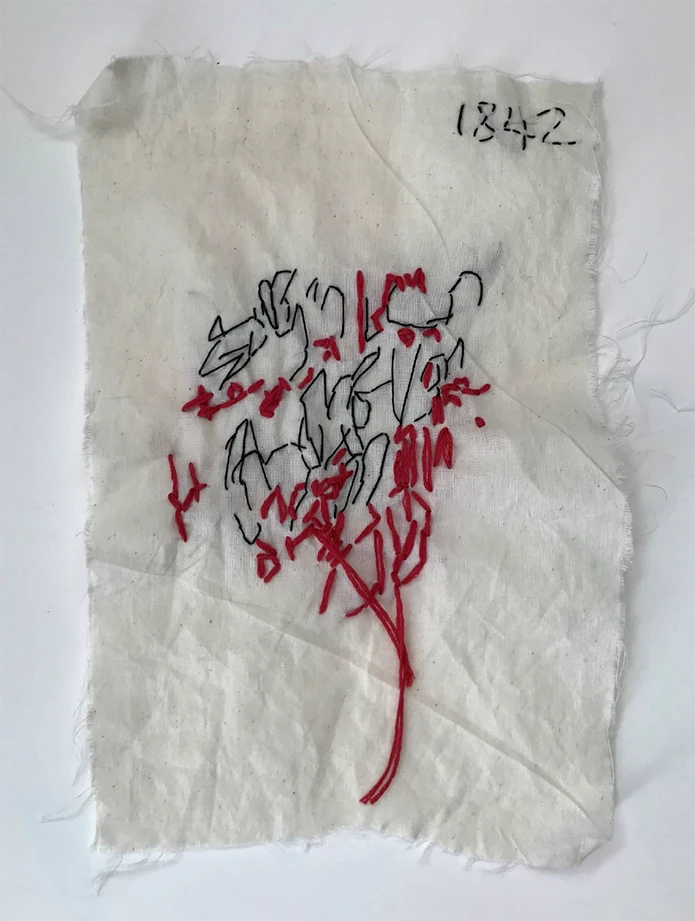

Nov 3rd, 1842

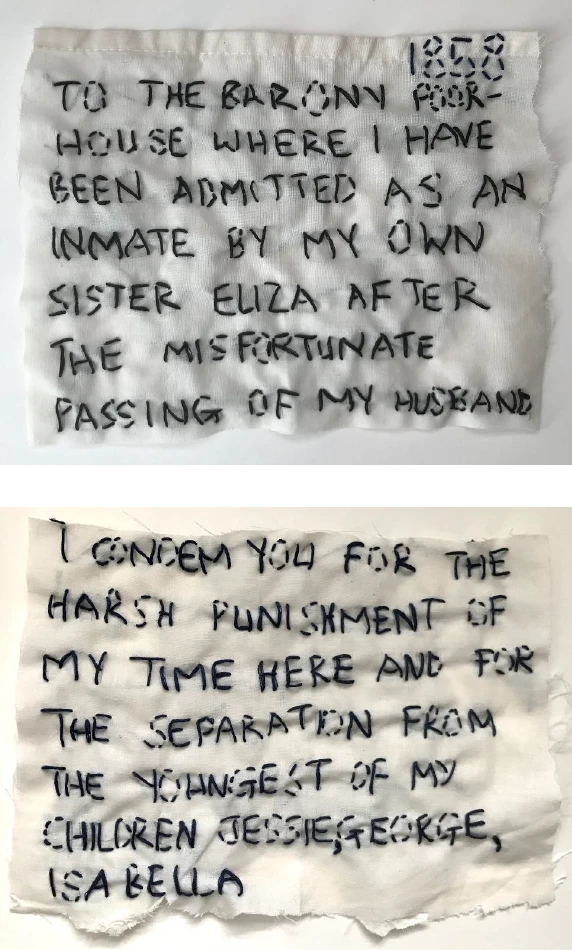

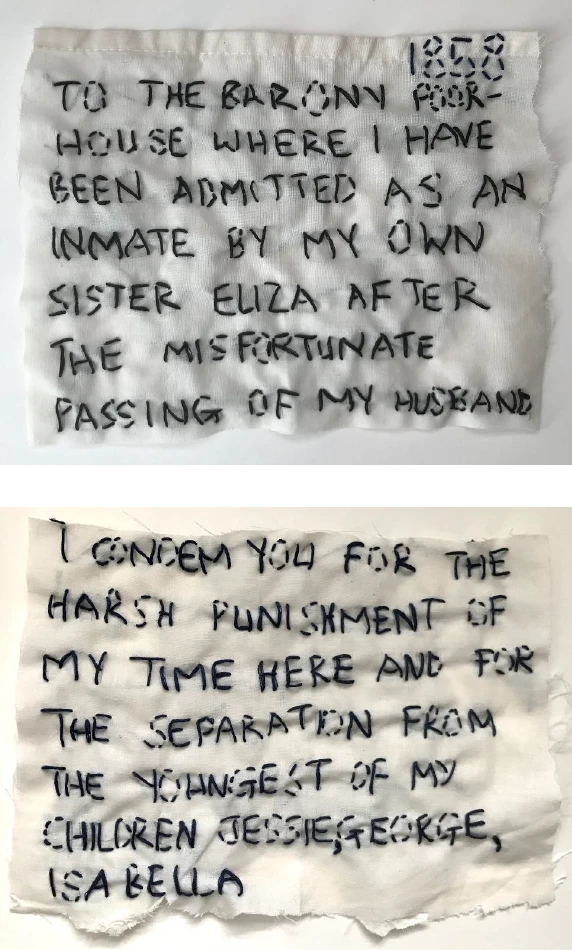

Sampler I and II, 1858

Commentary

When I received the copy of Grace Binning’s archive extract, it struck me that this was a relatively young woman, aged only thirty-one on admission into the Gartnavel Royal Asylum, with ten children from age five weeks to age fourteen. She had recently opened a shop with her husband and was believed to be suffering fatigue and anxiety from this also. Her symptoms were: mania, a want of sleep, believing she was talking to the devil, she was a queen, wanting a knife to cut her throat, incessant raving on all subjects, she destroyed clothing, bedding, furniture.

I felt a connection, and a level of empathy for Grace. What woman wouldn’t struggle in those circumstances? Although I understand large families were part of the norm back then, it sounded like a lot – ten children including a new-born, and a shop to run. Although she was a paying patient, at fifteen shillings a day, it sounds like poverty wasn’t apparently a factor at this stage. She stayed for fifteen days, whereupon her sister deemed her fit to leave, and she was prematurely dismissed.

I immediately felt inspired to record some of the details through textiles, which is an art form I express myself through, as well as writing. What sprung to mind initially was using a hospital or bedsheet. I also wanted to get a sense of the place where she had been, and despite living only ten minutes away from the grounds I had never seen the Asylum before. I ventured out on a few walks squeezed in around university and family commitments. It sunk in that somewhere in the grand yet oppressive buildings, Grace Binning had once been there. I stood looking into the empty, smashed windows, outside looking in, whilst she had been inside, looking out, or perhaps seeing only the room she was in. A chance encounter with an elderly hospital worker informed me that unmarried mothers were committed there, social misfits, not just those with mental health issues. He told me of years ago being inside the Asylum when a fire alarm went off and seeing orbs, how he’d felt quite spooked. He told me of Urban Explorers, people who go in these old buildings and take photographs. I left feeling intrigued to find out more.

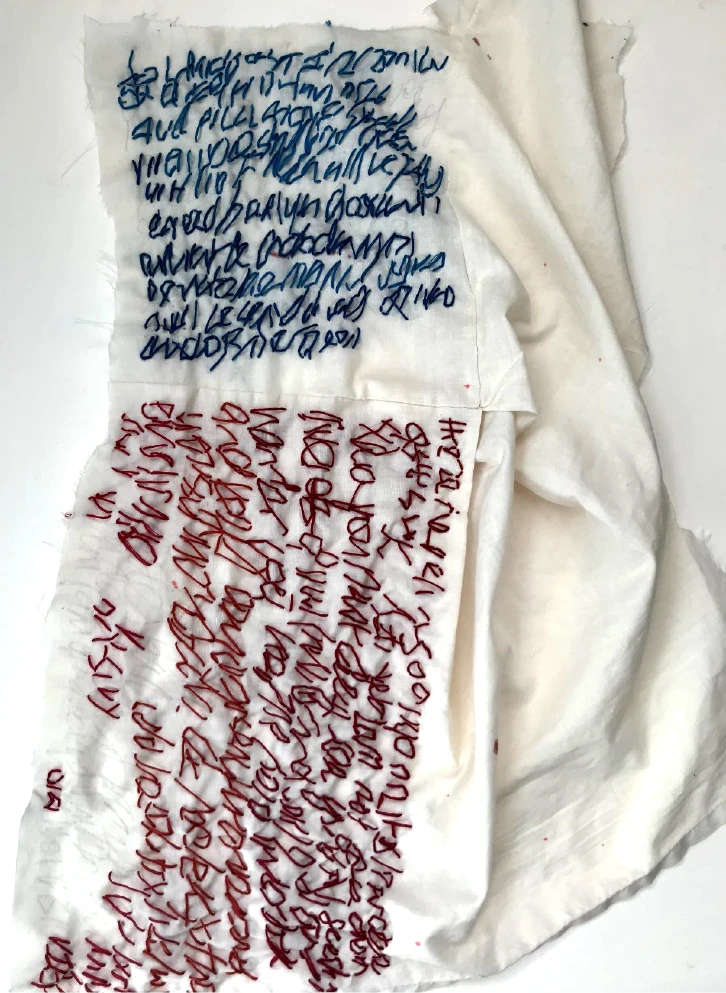

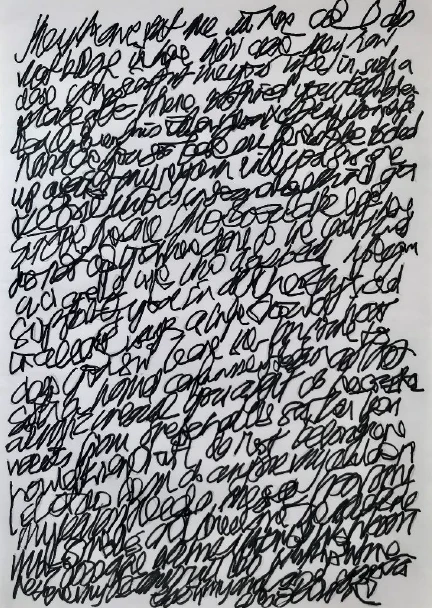

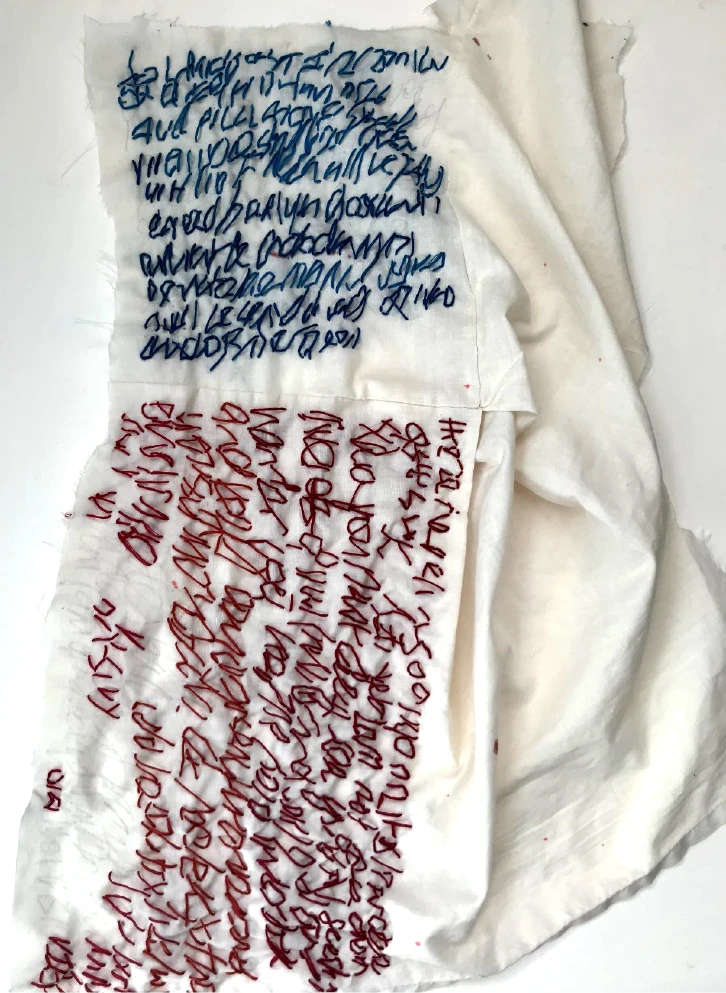

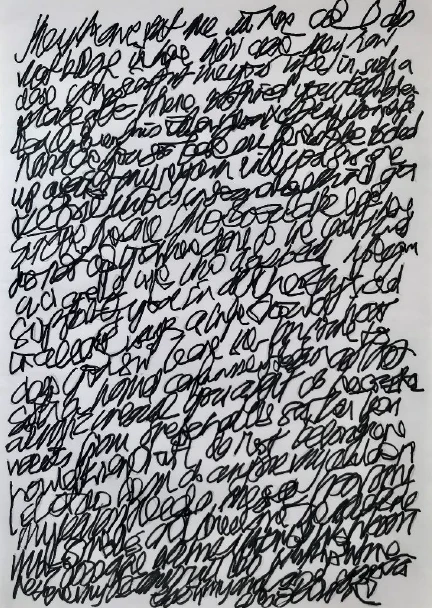

After reading the transcript of Grace’s admission, and a breakdown of her daily condition whilst at the Asylum, I decided I would create textile work as if it was Grace doing it whilst at Gartnavel. It felt like I was channelling her, her feelings, the mania, the exhaustion, the rage, onto the fabric. I tore up an old bedsheet as if she had done this perhaps taken from her hospital bed, and using the transcript, I did stitch work to document her visions, who she believed herself to be and the thoughts she was having. Asemic writing (writing without meaning), formed a large part of it, I wrote down the rage that Grace may have been feeling, then stitched on top of this. I also drew one on paper, words becoming illegible.

I was curious if there was any more information about Grace Binning out there. So, I dug a little deeper using basic name searches, then through Scotland’s People and Old Scottish Genealogy and Family History websites. The latter came up with a Grace Binning or Ewing (as she is described in the original archive) who had been registered on the General Register of Lunatics. I received two archive copies from them. The register archive stated that from the 19th of January until 9th of July 1858 she was in the Barony Poorhouse in Glasgow, and 17th January until 1st of May 1863 she was in the Glasgow City Asylum. In both cases she was marked down as pauper on arrival and recovered upon leaving.

I had thought that Grace’s visit to the Asylum had been a one-off occurrence, and although each stay was only brief, it disturbed me to read this. Especially the section on the Poorhouse – what had happened to her husband, the shop they had taken on, and her children? There are many blank spaces here. For the last part I decided her stitch work would be a smaller and more focussed sampler. I was already familiar with women such as Mary Frances Heaton and Lorina Bulwer, who had created stitch work whilst in an asylum or poorhouse.

It feels like there was injustice somewhere, that Grace Binning came to be in the poorhouse. She had ten children. I felt anger, that women didn’t receive help back then for contributing factors such as post-partum issues, or sheer exhaustion. It was an intense experience when sewing from Grace’s perspective; I felt a lot of strong feelings come up, not only for her, but for other women I had read about. There were times I had to put it aside as it caused me to become too emotionally connected to it. And it brought up, reminded me of, mental health issues that have affected my own family.

There are stories to be told from these blank spaces existing between Grace Binning’s admissions which are of interest for me and may be a future project.

Links to further information about women who created embroidery in asylums:

Embroidery tells the devastating history of women in Norfolk’s workhouses – Norfolk Live

[Patient record for Grace Binning, HB13/5/15]

R Fraser is an experimental women’s fiction writer and student of Textile Design at Glasgow School of Art, and she has an MLitt (Distinction) in Creative Writing from the University of Glasgow. Her written work has been published in journals such as Gutter, Litro, Quotidian and From Glasgow to Saturn; she’s a winner of the Bellahouston Prize and the Jessica Yorke Award and was shortlisted for the North Literary Agency Prize. She is represented by Laura MacDougall at United Agents.

Grace Binning responds

R Fraser

Conversation with the Devil

Daily Diagnosis

Cut, Tear, Scratch

Confined

An Address from Your Queen

Thank you Letter to My Sister (For My Immediate Removal)

Nov 3rd, 1842

Sampler I and II, 1858

Commentary

When I received the copy of Grace Binning’s archive extract, it struck me that this was a relatively young woman, aged only thirty-one on admission into the Gartnavel Royal Asylum, with ten children from age five weeks to age fourteen. She had recently opened a shop with her husband and was believed to be suffering fatigue and anxiety from this also. Her symptoms were: mania, a want of sleep, believing she was talking to the devil, she was a queen, wanting a knife to cut her throat, incessant raving on all subjects, she destroyed clothing, bedding, furniture.

I felt a connection, and a level of empathy for Grace. What woman wouldn’t struggle in those circumstances? Although I understand large families were part of the norm back then, it sounded like a lot – ten children including a new-born, and a shop to run. Although she was a paying patient, at fifteen shillings a day, it sounds like poverty wasn’t apparently a factor at this stage. She stayed for fifteen days, whereupon her sister deemed her fit to leave, and she was prematurely dismissed.

I immediately felt inspired to record some of the details through textiles, which is an art form I express myself through, as well as writing. What sprung to mind initially was using a hospital or bedsheet. I also wanted to get a sense of the place where she had been, and despite living only ten minutes away from the grounds I had never seen the Asylum before. I ventured out on a few walks squeezed in around university and family commitments. It sunk in that somewhere in the grand yet oppressive buildings, Grace Binning had once been there. I stood looking into the empty, smashed windows, outside looking in, whilst she had been inside, looking out, or perhaps seeing only the room she was in. A chance encounter with an elderly hospital worker informed me that unmarried mothers were committed there, social misfits, not just those with mental health issues. He told me of years ago being inside the Asylum when a fire alarm went off and seeing orbs, how he’d felt quite spooked. He told me of Urban Explorers, people who go in these old buildings and take photographs. I left feeling intrigued to find out more.

After reading the transcript of Grace’s admission, and a breakdown of her daily condition whilst at the Asylum, I decided I would create textile work as if it was Grace doing it whilst at Gartnavel. It felt like I was channelling her, her feelings, the mania, the exhaustion, the rage, onto the fabric. I tore up an old bedsheet as if she had done this perhaps taken from her hospital bed, and using the transcript, I did stitch work to document her visions, who she believed herself to be and the thoughts she was having. Asemic writing (writing without meaning), formed a large part of it, I wrote down the rage that Grace may have been feeling, then stitched on top of this. I also drew one on paper, words becoming illegible.

I was curious if there was any more information about Grace Binning out there. So, I dug a little deeper using basic name searches, then through Scotland’s People and Old Scottish Genealogy and Family History websites. The latter came up with a Grace Binning or Ewing (as she is described in the original archive) who had been registered on the General Register of Lunatics. I received two archive copies from them. The register archive stated that from the 19th of January until 9th of July 1858 she was in the Barony Poorhouse in Glasgow, and 17th January until 1st of May 1863 she was in the Glasgow City Asylum. In both cases she was marked down as pauper on arrival and recovered upon leaving.

I had thought that Grace’s visit to the Asylum had been a one-off occurrence, and although each stay was only brief, it disturbed me to read this. Especially the section on the Poorhouse – what had happened to her husband, the shop they had taken on, and her children? There are many blank spaces here. For the last part I decided her stitch work would be a smaller and more focussed sampler. I was already familiar with women such as Mary Frances Heaton and Lorina Bulwer, who had created stitch work whilst in an asylum or poorhouse.

It feels like there was injustice somewhere, that Grace Binning came to be in the poorhouse. She had ten children. I felt anger, that women didn’t receive help back then for contributing factors such as post-partum issues, or sheer exhaustion. It was an intense experience when sewing from Grace’s perspective; I felt a lot of strong feelings come up, not only for her, but for other women I had read about. There were times I had to put it aside as it caused me to become too emotionally connected to it. And it brought up, reminded me of, mental health issues that have affected my own family.

There are stories to be told from these blank spaces existing between Grace Binning’s admissions which are of interest for me and may be a future project.

Links to further information about women who created embroidery in asylums:

Embroidery tells the devastating history of women in Norfolk’s workhouses – Norfolk Live

[Patient record for Grace Binning, HB13/5/15]

R Fraser is an experimental women’s fiction writer and student of Textile Design at Glasgow School of Art, and she has an MLitt (Distinction) in Creative Writing from the University of Glasgow. Her written work has been published in journals such as Gutter, Litro, Quotidian and From Glasgow to Saturn; she’s a winner of the Bellahouston Prize and the Jessica Yorke Award and was shortlisted for the North Literary Agency Prize. She is represented by Laura MacDougall at United Agents.